The reality is no single interview format is perfect. Someone has a bad day. They’re too easily faked. They are problematic for people who aren’t neurotypical. They test the wrong things. They’re not respectful of time. Passion isn’t the same as skill.

Look. Interviews aren’t fun for anyone. The whole process from initial contact to final decision can easily take months, depending on timing, and if you have a bad day at the end? You’re toast. Make the wrong decision as the hiring manager? You’ve wasted your time, and now have to undo the damage.

The best you can do is have a clear process and clear expectations. Understanding what is important to your team and your organization is critical. This tells you what you are testing for, which tells you how to prepare your interviewers and set up the day fairly. There’s nothing worse as a candidate than spending your entire day taking questions from a random crew who clearly hasn’t talked about what is actually important.

What I was hiring for a Senior UX Designer role at eBay, I had a list of things I wanted:

- A true senior designer. This person needed to have the experience to work independently, present their work, and make the right decisions without constant escalation.

- A designer focused on connecting products and flows, and less about building a flashy UI. This was related to business tools and payment processing. We wanted someone who was into the complexity of interconnected systems, not someone who would complain that they didn’t have anything Dribbble-worthy.

- A designer who was willing to take and give a critique of work. This designer would be facing commentary from multiple teams who are likely to disagree with each other, possibly putting the designer in the position where they would be forced to get to the root problem and build consensus, or at least make it obvious where the true points of contention are. It was also important for us, as a team, to critique each other’s work directly and honestly, without causing or taking offense.

- A designer with good communication skills. They’ll be responsible for presenting and selling their work, as well as working with product partners across coasts and continents.

When evaluating candidates, we knew we were going to be turning down ‘great’ designers who didn’t otherwise match what we wanted. It might be unfair, but (for example) a candidate with severe anxiety or who refused confrontation would not work well in this particular role.

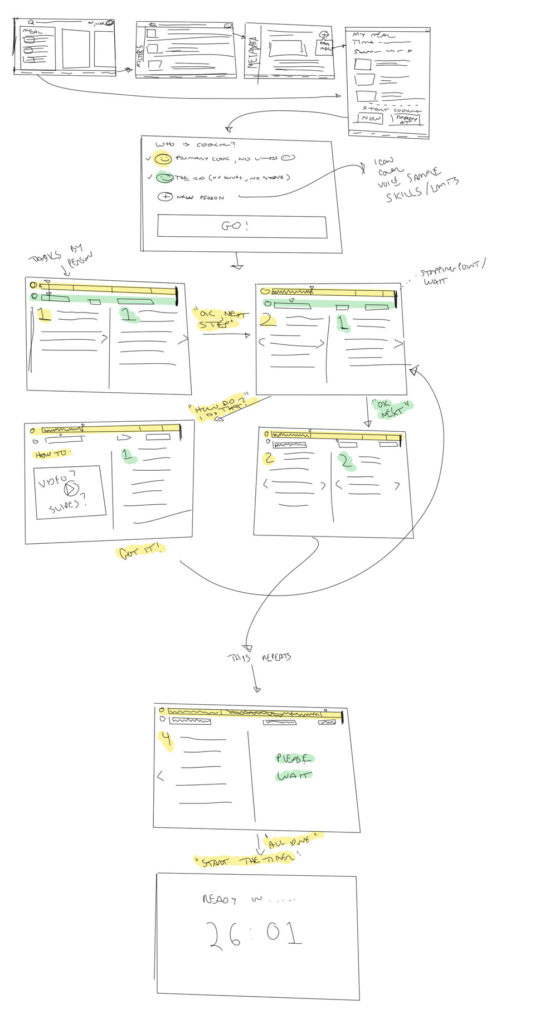

Designing the process

Usually, I’m a firm believe at starting with the end: know where you want to end up and design your flow to get you there. This is no different. In short, you’re going to have a candidate who you’re pretty sure you could hire come in and share themselves with the group. Once they pass the “recruiter sanity check” – they’ve verified the candidate is who they say they are, and they have at least some interest in the position, it’s time for a phone call or two.

As the initial non-recruiter contact, it’s your job to make a solid connection and impression. This is (probably) YOUR team, and (probably) YOUR hire. Give the details the recruiter didn’t. Make sure there are no illusions. And above all, make sure the candidate passes the sniff test. If you get a feeling that they’re glossing over something, push them on it. If there’s a gap, or something strange, dig into it. This doesn’t mean they’re a bad designer or a bad person, but that everyone has a blindspot. You’re trying to answer two questions with a moderate degree of confidence: Would I want to work with this person? Could they do the job? You’re screening for the needs that you’ve hopefully listed out, using an abbreviated form of your interview loop – end to end walkthrough of a project; they articulate a design process and perspective, the ability to participate in critique, and a general culture fit.

While I disagree with some of his examples of good and bad questions (and answers), generally, speaking I find Richard Carillo’s perspective agreeable: we need to give questions that provide room for thought and exploration, while still encouraging a candidate to provide an answer – even if it’s wrong. Take this question about reducing Rock, Paper, Scissors to two options: No special knowledge is required. You don’t have to create something from whole cloth. The candidate has a specific goal but will have to talk through how they get there.

Off-site

At this stage, I have never asked a user to spend more than an hour preparing anything. When reviewing work, I will happily review a project on a website, or a super-basic presentation as long as I can understand how you work, where you had an impact on the process, and how the final product succeeded (or failed) and how you might evolve it. Chances are, a designer preparing for interviews already has this ready, or can get it ready shortly. I repeat: I stress that I am not grading someone’s presentation design skills. I just want to walk through one project in detail, and ask questions. Beyond that, I’m going to ask pointed questions – talk through designing a new feature, with critique and iteration as we go.

I’ve also seen suggestions to ask candidates to “teach something they’re passionate about.” It’s an interesting request, though I struggle with it on principle. First, we’re interviewing a senior designer, not a manager or principal/lead designer. We’re testing the ability to do, not the ability to teach. Second, it’s incredibly hard to define success here even if they are a good teacher. What if they’re passionate about dance? Or astrophysics? I’m clumsy, and math isn’t my strong suit.

Your candidate passes the round of phone screens. You think they’re a promising candidate. But maybe they can’t show a lot of recent work due to NDAs. Maybe they don’t have a huge body of work. Maybe you’ve just been burned in the past. So you’re thinking, it’s time for a design exercise.

Design Exercises

Design exercises are a touchy subject. I did a few earlier in my career. I interviewed with design agencies when I didn’t have much of a portfolio, or at least had a rather scattered one, and I understand why. I spent days on them. One was given pre-interview and was the topic of much of our critique. There was no direction around expectations for deliverables or format – just “do this in 2-3 days”). If this sounds like a setup for failure, it was. To this day, I’m still not sure why they brought me in for an interview other than to spend hours tearing my work apart. I’ll leave them nameless because it sounds like they took the feedback to heart. Another was given after an interview. It was legitimately the kindest, best interview I’ve ever had, and the agency heads said they liked some of my work, but that it was inconsistent. They gave me an old brief, their final set of wireframes, and we chatted for a few minutes. A few days later, I sent my work to them… and they broke my heart. This was Huge, Inc. (in their independent days). To this day, I have nothing bad to say about this. I had a third, which gave me 24 hours to complete a full presentation, from scratch) – even though I had a full-time job at the time.

I recently completed an exercise before being hired at Indeed, and I have to say that I feel it was a pretty good example. It was made clear that this work as NOT meant to be used in their daily work. I was given a clear brief, and clear expectations as far as deliverables and scope. I was told how much time was expected of me, and asked when I could start and complete it. I was then allowed to present and discuss the work remotely – all of which minimized the actual disruption to my normal life. Also: I was paid (well) for my time. Do you need to do design exercises like this? No. Good candidates have been hired without them. But, if this is a part of your process, do it like this.

Onsite

Then, comes the big show: the onsite interview panel. Assuming your candidate has gotten this far, you should be pretty confident that they’re a good match because you’re about to wreck your team’s day.

I feel like UX and product design interviews have an almost standard flow and while I think that does lead to a bit of a cookie-cutter feel, it’s not a bad process. They’ll introduce themselves, and their background, and walk through 2-3 projects. The panel (who are all of your breakout session interviewers, as well as other interested parties) is going to watch politely and ask clarifying questions or ask for more information, but avoids outright critique. This is setup for the rest of the day and ensures everyone has the same background, besides testing the candidate’s ability to hold it together and tell a coherent story in front of a dozen people.

From there, you’ll break out into as many sessions as you have time and people for. Having been on both sides of the process, I feel that paired breakout sessions are the best. They allow you to expose more of the team without overloading the candidate, help eliminate dead spots in interviews and helps ensure that no single person can break the process. Also, the day’s schedule should, in general, be shared ahead of time. The panelists should all know exactly what they’re doing. The candidate should have a general idea of what to expect. Other than generally asking the panelists responsible for the candidate deep-dive to followup the presentation immediately, there’s no set order to the operation, and time should be left to allow the candidate to breathe – try ending sessions 5 or 10 minutes early, instead of on the hour (or half-hour).

Deep dive

Immediately following the presentation, go deep on the presentation. Ask critique the work, critique the decision-making, and make sure the candidate’s contributions are clear. Leave no stone unturned.

Whiteboard design sessions

Give the designer a brief, and ask them to solve a problem. This is almost cliche, and there are dozens of guides that teach the test. Yet, I can’t think of a better way to understand the ability of a designer to solve a problem. Whether you’re designing an app for a theme park, an autonomous vehicle product, or a video game scoring system, you want to understand if a candidate can break down the task in a way that works for your team, and produce a concept for a viable product or system at the end and with points for further iteration and AB . The guidance I can give here is that you must – MUST – push for both process and an actual solution. Too many UX designers can’t actually design experiences – they’re lacking the ability to synthesis knowledge, assumptions, and hypotheses into testable flows.

I don’t know if whiteboard sessions must always relate to your core product. What I do know is that they should stretch the designer’s apparent skill set and get them outside of their comfort zone – even if you have to do two whiteboard sessions.

Critique

I am a firm believer in the power of group critique among peers. With the right framework, this transforms designers and their work, improves decision making, and eliminates the need for putting designers in front of a firing squad of directors. I will always fight for this in any flow I design. Given an experience that’s fairly common and no personal stake in the matter, ask the candidate to provide critique. Try to understand the user and business needs behind a feature as designed, and discuss where it meets or fails those needs. We’re not looking to endlessly praise the subtle interactions of Google Maps, or destroy the endless consumption of Netflix. We’re trying to take on the perspectives of others, and provide honest, kind, and useful critique. If you’re short on time? Combine this with a whiteboard session,

Culture fit

I’ve already had my say here. Team fit is valuable, but you don’t want to create a monoculture. Test for cultural fit, but don’t be a jerk. If you’re short on time, you can do this separately.

Breaks

Allow for 5-10 minutes between sessions. And if you’ve got a full day scheduled, plan to take the candidate for lunch (or let them explore solo depending on your environment).

Wrap-up

Don’t just let the candidate walk. Ask how it went. Not everything will go perfectly, and some people will just have an off day and their brain will fall out for a few moments. A candidate who gets 95% of the way there and shows self-awareness about where they failed or could have improved might actually be the right candidate.

Be honest with the candidate about your timelines. If you’re in the final round of candidates and want to finish them all before deciding, say so. But be fast. I lost multiple candidates at eBay because our process took so long, and we can’t ask everyone to wait forever. In the meantime, get feedback within 24 hours. It doesn’t need to be immediate – allow time for parsing and reflection, but don’t wait so long the details fade. Look for areas of agreement and disagreement as much as the individual hire/no-hire ratings. And last, follow whatever HR-approved decision-making process you’ve got in place.